Rating scales are one of the most common survey formats and have been the subject of many studies. The following links will give you more insight into how to make the best decisions if you’re using a scale.

Two articles will give you a flavour of the original concepts in creating a rating scale

If you feel like diving into the original concepts in scale creation, then have a go at reading the papers. I found them easier to read than I expected, and if you read the original then you will avoid all the misunderstandings that are everywhere – including in peer-reviewed articles. The most famous of these is “Likert scales and how to (ab)use them” (Jamieson 2004) which prompted one of the most attacking papers ever: “Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and urban legends about Likert scale and Likert Response Formats and their Antidotes.” (Carifio and Perla 2007). In an ironic twist, Carifio and Perla attack Jamieson for not reading Likert’s original writings – but then quote two Likert references, one of which has nothing to with creating Likert scales.

There have been a number of good studies on negatively-worded statements

In the book I made the statement: “Broadly speaking, negatively-worded statements are harder to understand than their positive equivalents”. Negation turns out to be a fascinating, tricky, and widely-studied subject. I recommend these two well-referenced studies as a starting point:

“Negation: A theory of its meaning, representation, and use” (Khemlani, Orenes et al. 2012)

You’ll also find many studies of the best number of response points on a rating scale

My discussion of number of response points was sparse. Here’s a longer version:

Response formats with an odd number of points have a mid-point, which gets used by people for a variety of reasons including “undecided”, “do not understand the question”, “this does not apply to me” and (this one may be uniquely British) “it’s not appropriate for me to express an opinion on this”.

The choice of “undecided” has led to experiments on response formats with no midpoint, otherwise known as an even number – usually 4-point or 6-point formats. People who have a true answer but might be a bit reluctant to reveal it (remember ‘Decide’ in Chapter 4, Questions?) must pick one side or another – which is fine when that reluctance was the only reason for choosing a midpoint. If they were choosing the midpoint for any other reason, then unfortunately a ‘no midpoint’ response format means that you lose both of the central points as they will randomly choose either of them.

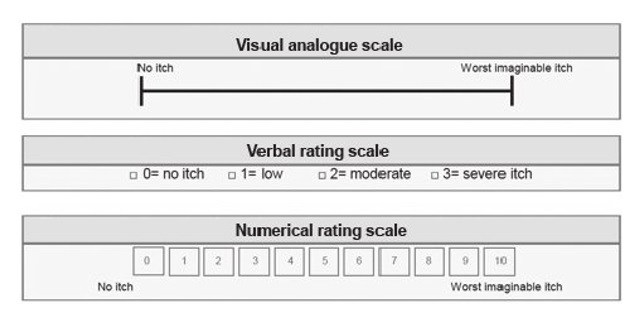

There are also arguments in favour of a higher number of points, often 7-point but increasing up to visual analog scales: a line where the person marks the answer they want, usually then turned into a number from 0 to 100.

There is some evidence that a greater number of points leads to more reliability (consistency of response over repeated use of the format) and some people who answer say that they prefer to have more choice. Against that, there’s the phenomenon of ‘clustering’ where people tend to choose only a few from the available points – also a possibility with 5-point and 6-point formats.

Feel that “pruritus intensity” is a bit too different from the sorts of questions that you want to ask? Don’t worry, there is plenty of research that uses questions that are much more general.

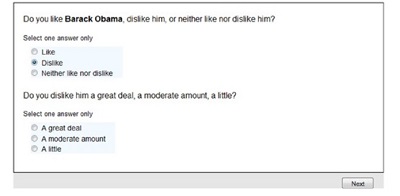

For example, (Debell, Wilson et al. 2019) tested three formats: the classic Likert-style statements with response points associated with each individual statement (“Single Item”), a grid, and a ‘branching’ layout. I’ve never seen the branching layout in a web survey, but the authors cite previous research that says it can be quicker and more reliable than other formats in phone surveys.

Guess what: they found that it didn’t matter very much. Well, to be accurate:

Branching is the loser in our tests. It takes the longest to complete and has the weakest criterion validity. It is also the most difficult to program and produces the least convenient data to work with because branching splits the answers to one question into two or three variables. We therefore find no reason to choose branching formats in internet surveys. (Debell, Wilson et al. 2019)

But between single-item and a (short) grid? They are close, and there are minor benefits of one compared to another depending on what you are trying to do in your survey.

Academics have also argued over whether to label response points with words or numbers

Another controversy that has been much researched: the question of whether or not to label the individual response points with words, with numbers, not at all, or to partially label them. There are many studies to look for and the answer is “it doesn’t matter very much”. For example, Sauro and Lewis (2020) tried fully labelled against partially labelled. They report their findings in ‘Comparing Fully vs. Partially Labeled Five- and Seven-Point Scales: https://measuringu.com/labeling-scales/ .

A question I’m sometimes asked about Likert scales

Question: “Since you’ve introduced this topic, do you think you ought to cover semantic differential and rasch type questionnaires as well? I see a lot of questionnaires attempting to use the semantic differential concept.”

Answer: The article Comparison of Item Formats: Agreement vs. Item-Specific Endpoints (Lewis 2018) on turning scales into direct questions is helpful. I got similar patterns of results twice when doing research for a client, but couldn’t publish their proprietary data.

That’s why I’ve always used just positive-tone items in the standardised questionnaires I’ve developed, and was gratified with the results Jeff Sauro and I got when experimenting with an all-positive version of the SUS: When designing usability questionnaires, does it hurt to be positive? (recently replicated, see Is it Time to Go Positive? Assessing the Positively Worded System Usability Scale (SUS).

And finally, further reading on Likert scales

The articles in Gary M Maranell’s Scaling: A sourcebook for behavioral scientists, span more than 40 years, leading up to the book’s publication in 1974. It’s therefore a good book to read to get a sense of the history of our thinking about measurement and scaling. The selection of chapters include classics in the field, such as Likert’s original 1932 paper ‘The method of constructing an attitude scale’.