This post is co-authored by Amy Hupe, Ignacia Orellana, and Caroline Jarrett.

“Use this because we said so” is not a convincing strategy for building trust with designers and developers who want to, need to, or are told to, use a design system.

“Use this because we’ve done research on why it works” is a more powerful argument.

In this post, we’ll describe the needs we discovered in our meta-research: user research with designers and developers about how they use the research that supports a design system – and what they need from it.

Then we’ll share some tips for how to incorporate research in your design system.

Good design systems rely on a lively community

A good design system relies on active contributions from the community of designers and developers who are using it in their work. The community’s challenges, suggestions, and experiences help the design system’s team to keep it relevant, current, and, most importantly, heavily used.

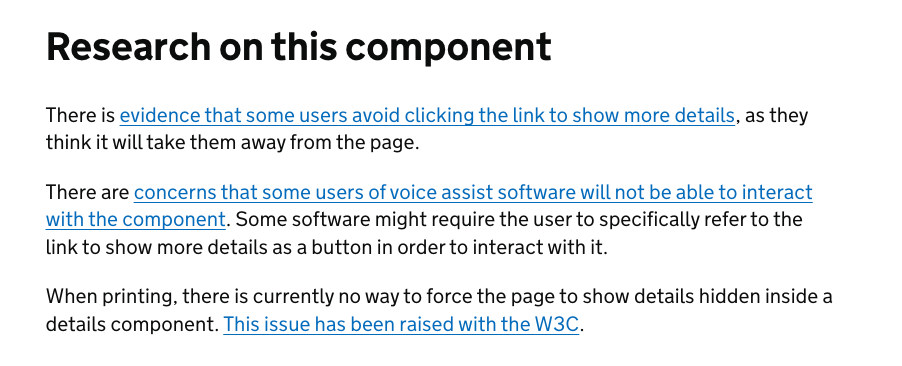

Describing the research that has – or hasn’t – been conducted for design system components and patterns helps the community to make informed contributions to the system. It also helps designers and developers make informed decisions on what to use and how much further development or testing is needed for the context of their product or service.

Designers and developers want to see research for different reasons

Even the most obedient designer or developer is unlikely to accept the entire system as suitable for their work in every detail.

From our research, we’ve observed designers and developers in government having different reasons for wanting to see research on a design system. The ones we’ve heard the most often, expressed as ‘needs’, are:

- I need to convince a manager or colleague to use this and I believe that research will help me.

- I think the service or system I’m working from is different from the one the design system team had in mind. I need to understand their research so I can decide if their choice is likely to be appropriate for me.

- I don’t agree with one of the things in this design system. I need to know what it’s based on before I decide whether to challenge it.

- I’m going to use something from this design system and I need to know what gaps need filling, or what to watch out for, when using it in my service.

- I need to see proof that this is accessible. I’ve been burned in the past by design systems that didn’t put enough effort into making sure that they would work for disabled people and for people who use access technologies.

Different needs often warrant different solutions. For example:

- Information about the number of services or sites already using a component or pattern may be sufficient for the person who needs to persuade a manager.

- Saying who took part in user research for a pattern and the service it was tried in may meet the needs of the person who has concerns about the component or pattern.

- A description of the research that has happened can be a starting point for designers and developers who are planning their own research. This helps them avoid repeating work that has already been done.

Sharing research in design systems is challenging

These different reasons for wanting to see the research on components and patterns in a design system mean it’s hard to find a way of sharing it that suits everybody.

And even when design system teams know what research is useful to share, they might find it difficult because they:

- lack the confidence to share what hasn’t worked

- are reluctant to admit when research hasn’t been done

- need to protect users’ privacy

- are working in an organisation where there’s lots of variation in how people conduct and document research.

It’s also challenging to research individual components and patterns. They usually need to be put into context to make sense, but this context can sometimes distract users and impact the findings. We’re planning to write another blog post soon where we’ll explore this in more detail.

Decide on the right level of detail

Design system teams must balance the need to evidence design decisions with the risk of overwhelming users with too much information.

The “right” level of detail will vary based on organisational culture and on how busy people are. For example, organisations where employees are expected to follow guidelines without question might not need to provide much rationale. But in an organisation that encourages people to challenge the status quo and share responsibility for the overall quality of its products, employees may expect more information.

Someone in a hurry may only have time to grab what they need and go. They don’t want to have to wade through a pile of research to get there.

To support these different needs, a good approach is to:

- stick to concise inline reasoning in component and pattern documentation

- put more detailed research somewhere else.

For example, in the guidelines for using a checkbox component, we might say something like:

“This checkbox has a touch target of 44px. Research shows this makes it easier for users who have issues with motor control to select it.”

We can then provide more detailed research in a separate place, for users who want to dig deeper. For example, in a research section at the bottom of the documentation page, or in a blog post that we can link to.

Use summaries and links

When deciding how to show research in your design system, be realistic. Let’s think about someone who wants to contribute research. We should consider:

- how much effort they’ll have to put in

- what tools they’re likely to have access to

- how much time it will take them.

A short summary of the research with links to more documentation (blog posts, articles, GitHub issues) lets people go further when they need to, without slowing down people who do not.

Be clear about what to aim for – but realistic about what’s achievable

We recommend a flexible approach. Aim for full research documentation where possible – typically for new additions and contributions. Accept that sometimes little or no research is available – typically, for older components and patterns where decisions were made some time ago and aren’t easy to trace.

When everyone knows how much research is expected for additions and changes and how to document it, it’s much easier to organise information and stick to what’s relevant.

For example, in the GOV.UK Design System team, Amy and Ignacia developed the following list of headings for research as “desirable”:

- Who developed the pattern or component

- Known issues and gaps

- List of services using the component or pattern

- Next steps (describing areas needing more research).

You can see an example of this applied to the ‘step by step navigation’ pattern, with all 4 areas described.

Sometimes, a design system team won’t have all that information. The GOV.UK ‘button’ component documentation, for example, has a much shorter research section. Nevertheless, we recommend having some evidence or rationale rather than none.

It is worth making the effort

Everyone involved in design systems – whether they’re a member of the team, a user of the system, or a contributor – knows that design choices are usually made based on a combination of:

- research

- design flair

- let’s be honest – often arbitrary decisions made in the interest of ‘getting something out there’.

A lively and questioning community of developers and designers helps to hold the design system team to account for their choices. This makes for a more representative, robust and reliable system.

If a design system does not describe the research behind components and patterns then it’s harder for a designer or developer who has concerns, or can’t find something they need.

Design system teams must give people the information they need to be able to ask questions, challenge choices, and put components and patterns in front of their users.

By being honest about what’s been learnt and what hasn’t, and what’s worked and what hasn’t, we can promote a more efficient way of working, and keep duplication of effort to a minimum.

This helps to foster a healthy culture of working in the open and encourages iteration, allowing teams to improve things collaboratively over time.