A version of this paper was first delivered at the 47th Society for Technical Communication Conference in Florida.

A version of this paper was first delivered at the 47th Society for Technical Communication Conference in Florida.

Most people do not enjoy filling in a form

If you want to create a usable form, the first step is to understand what a form is. By unpicking its elements, it is then possible to improve each aspect and put it back together in an improved state.

These ideas are derived from my evaluations of various types of forms, mainly my work with the United Kingdom Inland Revenue to improve the usability of our tax forms. I noticed that many people are worried by tax froms even when the form is still in its brown envelope with ‘On Her Majesty’s Service’ printed ominously at the top.

Tax forms are an extreme example, but usually people do not look forward to filling in a form. This paper begins with a discussion of a form, and explains forms in terms of three layers: appearance (layout), conversation (questions and answers) and relationship (the structure of the task).

A form looks like a form

From time to time, I ask people working with forms “what is a form?”. The question is not as easy to answer as it appears, and the answer usually starts with a long-drawn out “Weeeellll” or “I suppose it’s…” followed by something about collecting information, or questions and answers.

I suspect the problem with my question is that the answer is too obvious. We tend to know that something is a form because is looks like a form. Try these two examples. Both of them are pieces of paper with marks: coloured pen in one case, third generation photocopy in the other. Which one is the form?

Is it this one, with marks that suggest some fruit?

Or is it this one, a photocopy?

It’s an easy choice for most people. Even if the print is too bad to read, we know which one is the form: it looks like a form. It’s got spaces for the answers, and some text areas ahead of them that we assume are the questions. A form is something that looks like a form. This is the appearance layer of the form.

The appearance layer is what we interact with

The appearance layer starts with the paper or screen itself. On paper, we can see the size of the task: a single page, or the beginning of a booklet? On screen, it is more difficult to gauge the size. I suggest offering clues to the user, such as a note saying ‘page 1 of 4’ or ‘there are three sections in this form’. The alternative is to let them start on the form filling process, and then find it extends in an unexpected or unacceptable way.

We expect to see different areas within a form

Next, we have the printing – ink on paper, pixels on a screen. On a form, the text, lines, logos, and other elements tend to be viewed by users as three approximate, and sometimes overlapping, groups:

1. Page furniture: the bits around the edge, such as logos, form title, page numbers, and toolbars.

2. Instructions: text not directly related to questions and answers, such as welcome messages, descriptions of the form, offers of help.

3. Prompt/response pairs: the text of the questions and the answer spaces, perhaps grouped into bigger questions or sections.

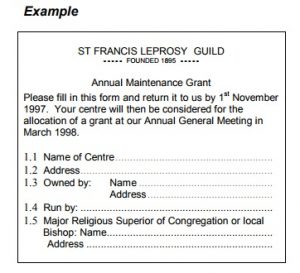

Here is the beginning of the form we started with. It starts with the charity’s name, date of foundation and address (omitted here for clarity), and the title of the form. All these are part of the ‘page furniture’.

We have 34 words of instructions, before the form moves into the prompt/response pairs with “1.1 Name of Centre”.

The prompt/response sequence continues with ‘1.2 Address’. As in many forms, these are not full questions, but short phrases prompting the user to supply an answer.

This form is filled in by hand or typewritten, so the dots give some guidance for where the writing should go: the response areas.

The page furniture surrounds the questions

In my experience, users decide which bits of the printing serve which purpose immediately they view the page. The typical user will identify that the page furniture exists without really taking it in.

Assume that your page furniture is invisible as the user starts work on your form. It will spring back into view when the user needs it – for example, when telephoning for help with the form. If you don’t have any page furniture, it can be disconcerting.

The instructions may or may not help

Having ignored the page furniture, the typical person may read some, all or none of the instructions. If the form is familiar, then the instructions are skipped altogether. As quickly as possible, they move into dealing with the prompt/response pairs.

As a rule of thumb, I suggest trying to keep your instructions to less than 100 words – approximately the length of the abstract for this paper. If you need to have more information than this at the start of your form, try using headings to break it into smaller chunks. Your user is likely to read the headings alone and skip the content beneath them, but at least they will know that there is material available on the topics you have covered.

The questions are prompt/response pairs

The prompt/response pairs create the question and answer sequence for your form. Before the user can start to understand the questions and supply the answers, they must be able to discern the prompt/response pairs. It helps if the text is easy to read. Good contrast between print and background, a simple typeface, and large enough print will all help.

We see the prompt/response pairs, but seeing is not enough

Although the appearance layer is what makes a form look like a form, it does not explain why forms are so difficult. As one person said to me: “It wasn’t the form that was difficult, it was answering the questions”.

Let us assume that we have provided our users with questions they can read, and move up a layer.

The conversation layer is about answering questions

A form is a document that asks questions and has space for the answers. This level makes more sense of the ubiquitous dislike of forms. People may not understand the question. They may find that the space for the answer is too small. They may have trouble deciding which questions apply to them, or be unsure which answer is appropriate or have difficulty finding the answer. This gives us the ‘question and answer’ layer in the model.

I call this the ‘conversation’ layer because the question and answer sequence of the form has many similarities with an ordinary conversation.

People have to understand each question

It helps the user if he can understand the question you are asking. As with an ordinary conversation, it helps if both parties share some common vocabulary and use it when talking to each other. Look again at my example form:

St Francis Leprosy Guild is a small Catholic charity that makes grants of funds to Leprosy centres in Third World countries. Although the phrase ‘Major Religious Superior of Congregation or local Bishop’ might seem obscure, it is clear in the Catholic context.

Problems can arise when the language is common but the meaning is different. This form had a pair of questions:

- 3.2 What leprosy control work do you do

- 3.3 With what results

The charity wanted to know about outreach programs where the centres try to find people with leprosy in the community and treat them. “With what results” was meant to get information about whether local population was responding to these efforts. However, most of the centres answered ‘rehabilitation and treatment’ for 3.2, and ‘good results’ for 3.3.

People then have to find an answer

Having understood the question, the user must then find the answer. Some of those answers are instant (“what is your name?”) but others require research. I do not have any difficulty understanding the questions on my tax return, because I have worked with those forms for a few years now: but digging out the financial papers with the answers is another matter.

When designing your form, think about where the answer comes from. Is this information you would expect a person might hold in their head? Or will they have to find it from another person, or another organisation?

People have to place the answer

The final step in the conversation layer is putting the answer onto the form. It helps the user if the space provided is appropriate for the answer. Too small a space is like cutting off the conversation while your respondent is still speaking. In my example form, the space for ‘name’ and ‘address’ was the same – but addresses are usually much longer than names.

Too big a space can create uncertainty in the user’s mind. If my answer is short, but your response area is large: have I misunderstood your question?

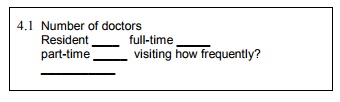

Offering boxes to tick, or radio buttons in an on-line form, saves effort for your users when placing the answer – but only if the answers you provide align with the answers they want or need to give you. On the St Francis Leprosy Guild form, we offered fill in areas for ‘Number of doctors’ like this, with a space for the numbers after what we considered to be the main types of doctor.

This was fine for most centres, but created a problem for one centre where they had no visiting doctors at all but instead took residents to the nearest hospital when they needed treatment.

It can help if you offer a choice of ‘other’ to let your user supply a different answer.

A conversation works better when it has “Unity of topic”

In a face-to-face conversation with friends, we often jump from one topic to another, mixing them together and back-tracking.

A form is more like an office meeting, where it helps to keep to one topic at a time. Jumping back to old matters can seem discourteous. Asking questions about two different things at the same time can be confusing.

A single topic to you might be two or more topics to your users. On the St Francis Leprosy Guild form, we asked about the treatment offered by the centre. This seemed like a single topic. However, there are three stages in treating people with leprosy: finding them, curing the disease, and helping them to learn how to cope with the disabilities the disease has inflicted on them.

Some people will be able to return to their communities, but others need long term care because of their disabilities. Some centres do all these types of work, but others do not: so it confused them when we asked one single question.

Put topics in a sensible order

A form forces a conversational order onto the customer. Think about supplying information to a person across a desk, compared to supplying the same information to a form. With a person, there is usually some possibility of discussion, changing the order of questions, asking for clarification, dealing with the topics that are relevant and finding a route around topics that are irrelevant.

A form is just as much an interview – but its order is fixed, the structure is in place. The person attempting it must adapt.

The problem is less acute on a paper form, where no one will know if you filled in some boxes at the end and then went back to the middle. In an on-line form, it can be difficult to save the form partly completed or to tackle it in a different order to the one the programmer envisaged.

The conversation has a context

When people say “I’m not good with forms” on the whole they are not confessing to trouble with reading, or an inability to write on paper or tick boxes. They are usually thinking about the conversation layer – although of course they would not use those words. They mean that they are “not good” with the process of getting the form, finding the answers and dealing with the consequences.

But the conversation and appearance layers do not explain all the form issues. Why do I feel more worried when I sign my name on my tax return than I do when supplying a signature for a parcel delivery? The questions and the answers are the same, and the tax return has a bigger box to sign in. It seems to me that we need a further level to explain this.

The relationship layer is about purpose

A form represents one step in an overall relationship between the organisation issuing it, and the user completing it. I suggest the term ‘task structure’, meaning the way the form represents a division of work between the issuer and the user.

The relationship and task structure create choices for the form user: about whether or not to put the answer on the paper, whether to fill in the form immediately or some other time, whether to bin it or return it. There may be consequences of filling in the form: fines to be paid if you are late with a tax form, goods to be delivered if you fill in an order form correctly.

The information exchange happens for a purpose

A form creates an exchange of information. If the organisation already holds some of the information it needs, then it can achieve a better task structure by offering that information back to the user for checking rather than asking for it again.

Let me give an example. A recent direct mail approach had a ‘personalised’ letter, sent to me at my business address. “Dear Mrs Jarrett” it said. “Your business Effortmark Limited will benefit…” and goes on to describe its offering. Then I turn the page to find a form that asks for my name, business name, and address – information that they clearly know already.

You can improve the information exchange of the form if you make the best use of the information your organisation already holds. Present back to the user the items that are appropriate to the task the form is undertaking. The user’s full credit history may not be tactful at the point you are asking them to sign up for another sale – but asking for name and address from a continuing customer shows a lack of respect.

The form is part of a power relationship

The final element to consider in the form is the power relationship between the organisation and the user at the point the form is presented and completed. A sales order form and a product registration card ask for very similar information: type of product, name and address. Maybe the order form asks for payment details and the registration card for reason for purchase.

Order forms are intrinsic to the purchase of the product, and therefore will be filled in. If the person confronted with the form wants the product sufficiently, somehow they will complete the form. The power rests with the organisation offering the product.

Conversely, registration cards have a low return rate. The user has the product, and can choose whether to fill in the registration card. At this point, the benefit offered by the form is much lower. Organisations typically try to entice the user to fill in the form by offering some benefit, such as entry in a prize draw or update mailings. The power rests with the product purchaser.

Considering the shift of power in the relationship can help you to decide when to try to collect different types of information. For example, if you think your purchasers are likely to have a strong desire for your product, you might try to find out reason for purchase at the point of purchase rather than during customer registration.

The charity thought about information exchange

In the St Francis Leprosy Guild form, the power lies with the charity as it holds the funds. But it wants the centres to apply: many of them get almost no funding anywhere else, and sustain impressive programs on small amounts of money. A typical centre in Tanzania sustains 65 residents on an annual budget of less than US $20,000.

The charity decided to continue to ask mostly for the same information as before, even though it held some of it already. They felt that the centres would be reassured by some questions that were familiar. But they deleted the questions that produced unhelpful answers, and replaced them with questions that asked for changes from the previous year. This helps the charity to offer funds for increasing needs. They also asked about other sources of funds: this helps to encourage the centres to develop their own resources, and the charity to decide how important its grant is compared to other sources.

The example shows that the effect that the overall relationship can have on the form, and how choosing questions can be a more complex matter than deciding on wording.

The layers blend together

Think about the three layers – piece of paper, question and answer, and task structure. I have used the word ‘layer’ because each level rests on the previous one. You cannot have the question without the paper it is printed on. You cannot have a task structure without the words that convey the task. The word ‘layer’ could also be misleading.

These layers are not separate in the way the two slices of bread are separate from the filling in a sandwich. It is better to think of the layers as the three ingredients in a cup of coffee: cup, coffee and water. The cup is the piece of paper’ layer. It should be possible to choose an attractive cup that is easy to hold. The cup is essential, but it is not a cup of coffee until something is put in it. On a form, you have your screen or paper, font, page furniture and colour scheme – but it is not yet a form.

The coffee is the ‘question and answer’ layer. You can use better or worse coffee or change the blend. On your form, you add questions and spaces for answers, think about their meaning, and consider where the answers come from. You can choose better words, change the order, add more of them or take them away.

The hidden ingredient is the water. Somewhere water got added to those coffee grounds, or instant granules. The water is an invisible ingredient – we simply assume that it is there, and yet bad water will create a bad cup of coffee, no matter what we do to the cup. Similarly, it won’t be a form until it has a task structure: a reason why it is sent out, and a purpose to fullfil. It only exists because there is a relationship between the form issuer and the form filler, no matter how transient that relationship might be.

Finally, you must have all the ingredients together. When we get poor quality, murky coffee in a leaky cup, we assess the overall experience – not each part separately.

Improve usability by layers

To design a more usable form, I suggest looking at each of the layers.

Look at the overall relationship:

- Why are you asking these questions?

- Is the question appropriate at this point in the relationship?

- Could you get the information some other way?

- Are you asking your user to do work that your organisation could do instead?

Consider the form as a conversation:

- Put the questions in the right order: reason for the form at the front, what to do with it at the end.

- Think about where the answer comes from.

- Group topics according to the origin of the answer.

- Provide answers where possible, but let your customer over-ride your choices of answer.

- Provide answer spaces that align with the size of the answer.

Finally, revisit the appearance:

- Use headings and colour to group areas of the form into topics.

- Expect your users to start work on prompts and response areas as fast as they can.

- Do not expect your users to absorb information presented in page furniture.

- Choose your instructions carefully, making them as short as possible.

- Use a font they can read.

A good form needs to be good in three ways

The three-layer model attempts to explain forms in terms of their appearance, question-and-answer sequence and task structure. Although the initial appearance is important, and the question-and-answer sequence is the most obvious part of the form, I suggest that in the end a good form needs a good task structure.

Extracts from St Francis Leprosy Guild forms used with permission. St Francis Leprosy Guild is a United Kingdom registered charity number: 208741

#forms #formsthatwork