Surveys often include questions about satisfaction. But what is satisfaction: an emotional response? all about comparisons? And what does it mean for user experience?

This article, first published in the November 2012 UXMatters, examines what satisfaction means and how best to handle its complexity in a user survey.

An unsatisfying way to ask about satisfaction

Recently, Janet Six devoted the October edition of her Ask UXmatters column to customer feedback surveys. That column has inspired me to have a go at one particular aspect of customer feedback in more detail: asking about user satisfaction. That and the excerpt from an email message, shown in Figure 1, which I received after an encounter with a customer support facility, complete with its odd repetition of the question.

The message in Figure 1 equated good support with satisfied; bad support with unsatisfied. What if a polite and charming support person were forced to explain a deeply annoying business rule to me? I’d be a mixture of conflicting emotions and would probably want to answer what: perhaps good, but unsatisfied?

Satisfaction Is an emotional response

Richard L. Oliver delves into human emotions—and every other aspect of satisfaction—in his classic text Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. He points out that the state of satisfaction may include a variety of emotions and that their intensity may vary according to how much you care—or putting that into psychological language, on a person’s level of engagement (arousal) or disengagement (quietude). This can make it tricky to understand what satisfaction means:

“It appears that emotional extremes including delight, excitement, and distress are naturally occurring emotions in satisfaction…. If a consumer responds that he or she is satisfied, does it mean that this consumer is in a state of contentment, or of pleasure, or of delight?”— Richard L. Oliver

Or putting this more simply: if you’re really interested in something, being satisfied with it might fall somewhere between being pleased and delighted; but if you’re not, being satisfied probably puts you somewhere between being pleased and relaxed.

Satisfaction is all about comparisons

When making a comparison, it’s not just how much you care; it’s what you’re comparing something with. To be satisfied, you’ve got to do some mental processing of an experience—to compare it with some sort of mental idea or standard of what the experience ought to have been like.

For example, bronze medal winners tend to be happier than silver medal winners, as depicted in Figure 2 and as described by Victoria Husted Medvec, Scott F. Madey, and Thomas V. H. Gilovich in their 1995 study, When Less Is More: Counterfactual Thinking and Satisfaction Among Olympic Medallists.

A 2006 replication of the study explained it like this:

“Winning any medal in Olympic competition is an amazing accomplishment. Folk beliefs suggest a linear decrease in positive emotions, with the gold medallists experiencing the most, followed by the silver medallists, and then bronze. However, in reality, [in Judo] the silver medallist loses the gold medal match, and the bronze medallists win their last match, capturing the bronze and avoiding going home without a medal…. Bronze medallists from the 1992 Barcelona Games appeared happier than silver medallists at the end of the match and on the podium, and … silver medallists’ comments were much more characterised by counterfactual thinking about ‘what might have been’ and were associated with greater regret and less enjoyable emotion.”— From D. Matsumoto and B. Willingham’s ‘The Thrill of Victory and the Agony of Defeat: Spontaneous Expressions of Medal Winners of the 35 2004 Athens Olympic Games’, from the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, September 2006.

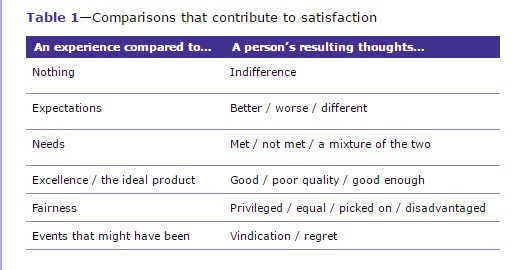

Richard L. Oliver delves into the varieties of factual and cognitive comparisons that can contribute to satisfaction or dissatisfaction, which I have summarised drastically in Table 1. He points out that, if you don’t process the experience at all, the result is indifference—not dissatisfaction.

Memorable experiences are also complex

Memorable experiences are also complex

If the emotions in satisfaction are complicated, what about the experience that gives rise to them?

Let me tell you a story about a rather simple experience. Today, I’ve used a whole bunch of websites: I bought some stuff. I browsed some stuff. I checked the news. But the experience that stands out as memorable: signing up for a website to which I’m going to log my routes and training for a half-marathon.

Was the experience satisfying? Well, yes and no. Looking at it through the lens of the different comparisons that affect satisfaction from Table 1, where did I start?

- I expected it to be straightforward. Registering for a website should be simple these days.

- I needed it to be reassuring. This half-marathon is double the distance I’ve ever attempted.

- Ideally, I wanted it to be inspiring—to suggest ways of conquering this training challenge in ways that I hadn’t yet thought of.

- I feared that it would be too US-centric and wouldn’t understand that I need to be treated a bit differently because I’m a UK-based person.

- If I hadn’t signed up for this site, I’d have had to go hunting for another one. Plus, over a few months, I’d already invested effort getting familiar with this site as an unregistered guest, so looking elsewhere seemed like a lot of work.

And where did I finish? With mixed results. It was mostly easy, but part-way through, there was a bit where I ended up paying a very modest fee to remove an ad. I had thought I was paying to use the site ad free, but then there appeared to be a fee to remove a particular ad rather than remove all advertising. Grumpily, I thought about spending time to find a different option. Later, I realised that I needed to sign in, so the site would know that I’d paid. Just a few bumps along the road, but they tangled me up and undermined the initial experience. Looking back, I had:

- multiple goals—signing up, intentions about long-term use, meeting a personal challenge

- multiple levels of effectiveness—completing the signup, paying the fee, my initial use of the service, my long-term use

- a variety of types of resources—the actual payment, my time, my emotional reaction to the mix-up

- multiple contexts of use—while it was just me at my desk, there are so many different contexts of who I am as a person: beginning runner, UK person, UX consultant, supporter of a particular charity.

So, on a scale of 1 to 10, how satisfied am I? You answer for me! Your guess will be at least as accurate as mine. The point here: memorable experiences tend to be complex ones.

The opportunity for satisfaction in a survey: focus

With all this bad news about complexities, is there any point trying to ask about satisfaction in a survey? My view: yes, definitely. The key is to pick one small aspect of satisfaction, and ask about that. Briefly. And provide space for a free-form comment.

Find out about users’ contexts, a bit at a time

When I was first collecting stories about how UX experts use surveys in their work, Suzanne Boyd of Anthro-Tech told me about asking one simple question: “Why did you come to this website today?”

They’ve achieved great results from asking this question, and that makes a lot of sense to me. It’s an easy question, and it explores one of the most important aspects of user experience: the user’s goals.

Of course, it’s tempting to go on to ask about all the other aspects of a visitor’s experience at the same time. Many of the worst surveys that I see do that—apparently taking the view that, if they’ve managed to grab my attention “to answer this short survey,” I’ll be prepared to answer screen after screen of questions about all sorts of details.

Don’t fall into that trap. Instead, keep your respondents happy by asking just a bit at a time—and not every single time they visit your site either. You’ll gradually build up the details that you need.

Ask about their recent, vivid experiences

People are much better at reporting how they feel right now and what they’re doing right now than on their experiences from days or weeks ago. Try to answer these two questions:

“Did you print anything in the last hour?”

“How many pages did you print last month?”

Most of us find it much easier to answer the first question and are much more likely to give an accurate answer. But an easier question than either of these might be:

Did you buy a printer this week?

For most of us, printing is a rather frequent and somewhat trivial task, whereas buying a printer is a rather unusual, more important, and therefore, more vivid task. The more trivial the experience, the less memorable—so the less accuracy you’ll get in people’s answers about it. Try to ask about recent, vivid experiences.

Ask a sample, not everyone

If you ask every customer to provide feedback, every time they visit your site, that’s a feedback form, not a survey. You know that, your respondents know that, and this contributes to declining response rates and poorer quality data—for both your feedback forms and your surveys.

Ask fewer people, and make it clear that you’re deliberately asking only a specific few. They’ll feel more special and be more likely to respond.

For any survey: interview first

Often, stakeholders consider that it’s quicker to put together a quick survey than to go out to find users and meet them face to face. Or even worse, they might say, “Let’s do a survey, then do some follow-up interviews.”

Survey methodologists do agree that a successful survey should always include an interview stage, during which you explore the topics of the survey in detailed interviews with typical respondents. But the interview stage should always happen early in the survey process. Interviewing first saves so much time because:

- It helps you avoid problems like asking questions that users don’t understand or don’t have answers for.

- It gives you preliminary data from the interviews that may be enough to move your project forward without the expense of an actual survey.

Summary

Satisfaction is a complex emotion, and memorable experiences are also complex.

Don’t try the patience of your survey respondents with long questionnaires that probe every aspect of those complexities. Instead, you should:

- Find out about users’ contexts—a bit at a time.

- Ask about their recent, vivid experiences.

- Ask a sample, not everyone.

- And as with any survey: interview first.

Acknowledgement—Thanks to Francis Rowland for the sketches. Image of printer by Kevin Cortopassi, creative commons

Slides from this presentation follow: